Symposium To Teach Young Scientists How To Replace Animals In Experiments

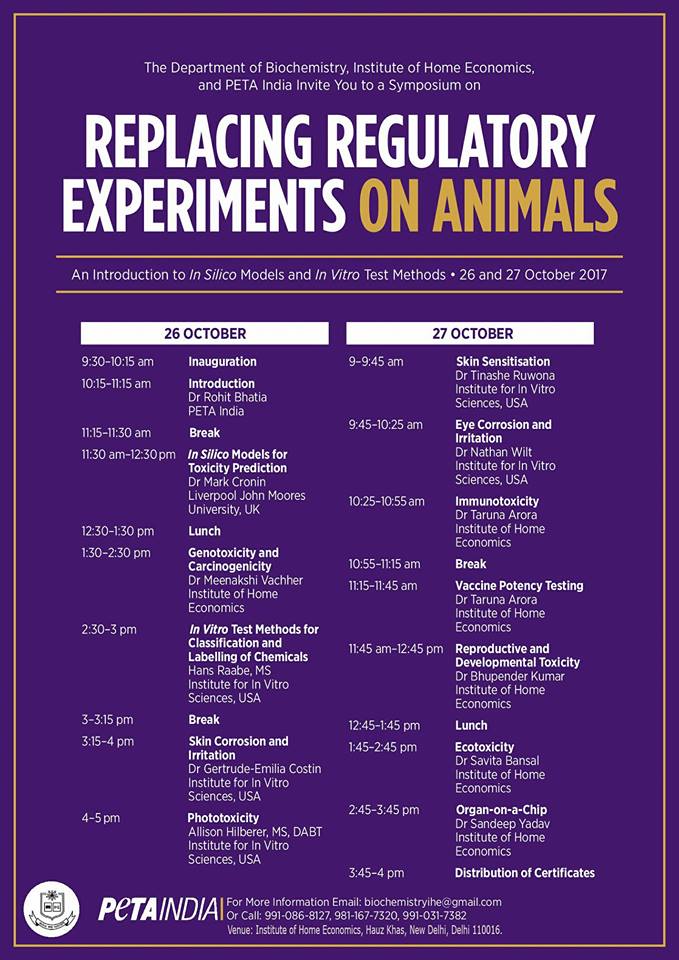

On Thursday and Friday, PETA India and the Department of Biochemistry at the Institute of Home Economics, a college of the University of Delhi, will be holding a joint symposium titled “Replacing Regulatory Experiments on Animals: An Introduction to In Silico Models and In Vitro Test Methods.”

Geared towards students who will complete tertiary studies and go on to become the next generation of scientists, PETA’s two-day workshop will introduce life science students to modern, animal-free testing methods that they can use to meet regulatory requirements. The workshop will highlight the scientific limitations of poisoning and killing animals in product tests, as well as the relevant ethical issues, and discuss the specific human-relevant models that can be used in tests for toxicity, carcinogenicity, skin erosion, and more.

Methods to be studied during the two-day workshop include in silico, or computational, models for toxicity prediction, which can provide information regarding the hazard potential of a chemical without animal testing. These methods include databases to retrieve toxicological data as well as Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships, which can identify hazard potential.

Students will also discuss animal-free methods for assessing a compound’s potential to cause cancer or mutagenesis, such as the Ames, in vitro (or “test tube”) micronucleus, and chromosome aberration tests. Other sessions will reveal how in vitro testing methods can be used to assess phototoxicity, or whether a substance becomes more toxic in the presence of light, and replace irritancy tests, in which chemicals are applied to an animal’s eyes or skin.

Other lectures will discuss a variety of non-animal tests for vaccine potency testing, reproductive and developmental toxicity, immunotoxicity, ecotoxicity, and more. Students will also learn about the latest progress in “organ-on-a-chip” technology and how these chips can be used for toxicity prediction.

PETA notes that because of the vast physiological differences between humans and the animals used in regulatory tests, the results of animal tests are often misleading.